INTERACT WITH HISTORY

It is the late 1890s. The American West is the last frontier. Ranchers, cowboys, and miners have changed forever the lives of the Native Amer- icans who hunted on the Western plains. Now westward fever intensifies as “boomers” rush to grab “free” farm land with the government’s blessing.

What do you expect to find on settling in the West?

Examine the Issues

• What might be some ways to make a living on the Western frontier?

• If native peoples already live in your intended home, how will you co-exist?

• How might settlers and Native Americans differ regarding use of the land?

Zitkala-Ša was born a Sioux in 1876. As she grew up on the Great Plains, she learned the ways of her people. When Zitkala-Ša was eight years old she was sent to a Quaker school in Indiana. Though her mother warned her of the “white men’s lies,” Zitkala-Ša was not prepared for the loss of dignity and identity she experienced, which was symbolized by the cutting of her hair.

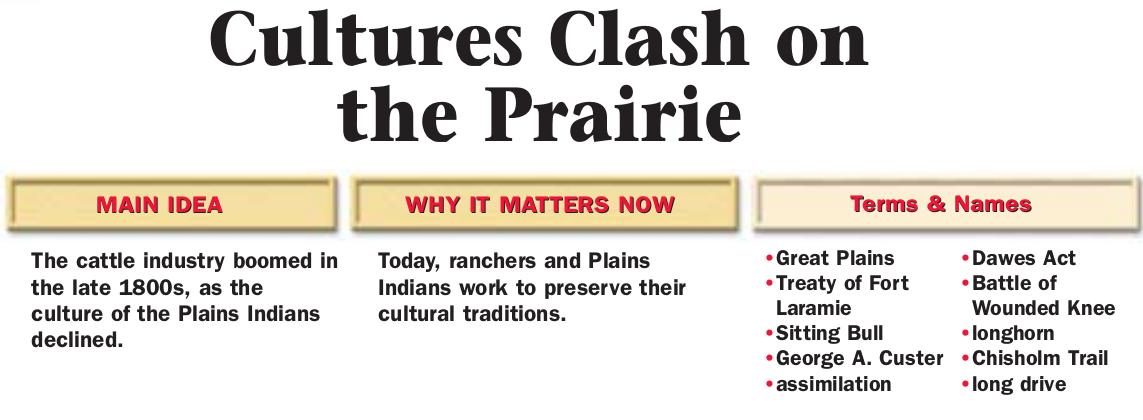

The Culture of the Plains Indians

Zitkala-Ša knew very little about the world east of the Mississippi River. Most Easterners knew equally little about

the West, picturing a vast desert occupied by savage tribes. That view could not have been more inaccurate. In fact, distinctive and highly developed Native American ways of life existed on the Great Plains, the grassland extending through the west-central portion of the United States.

To the east, near the lower Missouri River, tribes such as the Osage and Iowa had,for more than a century, hunted and plant-ed crops and settled in small villages. Farther west, nomadic tribes such as the Sioux and Cheyenne gathered wild foods and hunted buffalo. Peoples of the Plains, abiding by tribal law, traded and produced beautifully crafted tools and clothing.

FAMILY LIFE

Native Americans on the plains usually lived in small extended family groups with ties to other bands that spoke the same language. Young men trained to become hunters and warriors. The women helped butcher the game and prepared the hides that the men brought back to the camp; young women sometimes chose their own husbands.

The Plains Indian tribes believed that powerful spirits controlled events in the natural world. Men or women who showed particular sensitivity to the spirits became medicine men or women, or shamans. Children learned proper behavior and culture through stories and myths, games, and good examples. Despite their communal way of life, however, no individual was allowed to dominate the group. The leaders of a tribe ruled by counsel rather than by force, and land was held in common for the use of the whole tribe.

THE HORSE AND THE BUFFALO

After the Spanish brought horses to New Mexico in 1598, the Native American way of life began to change. As the native peoples acquired horses—and then guns—they were able to travel farther and hunt more effi-ciently. By the mid-1700s, almost all the tribes on the Great Plains had left their farms to roam the plains and hunt buffalo.

Their increased mobility often led to war when hunters in one tribe tresassed on other tribes’ hunting grounds. For the young men of a tribe, taking part in war parties and raids was a way to win prestige. But a Plains warrior gained more honor by “counting coup” than by killing enemies. This practice involved touching a live enemy with a coup stick and escaping unharmed. And sometimes warring tribes would call a truce so that they could trade goods, share news, or enjoy harvest festivals. Native Americans made tepees from buffalo hides and also used the skins for clothing, shoes, and blankets. Buffalo meat was dried into jerky or mixed with berries and fat to make a staple food called pemmican. While the horse gave Native Americans speed and mobility, the buffalo provided many of their basic needs and was central to life on the Plains. (See chart on page 207.)

Settlers Push Westward

The culture of the white settlers differed in many ways from that of the Native Americans on the plains. Unlike Native Americans, who believed that land could not be owned, the settlers believed that owning land, making a mining claim, or starting a business would give them a stake in the country. They argued that the Native Americans had forfeited their rights to the land because they hadn’t settled down to “improve” it. Concluding that the plains were “unsettled,” migrants streamed westward along railroad and wagon trails to claim the land.

THE LURE OF SILVER AND GOLD

The prospect of striking it rich was one powerful attraction of the West. The discovery of gold in Colorado in 1858 drew tens of thousands of miners to the region.

Most mining camps and tiny frontier towns had filthy, ramshackle living quarters. Rows of tents and shacks with dirt “streets” and wooden sidewalks had replaced unspoiled picturesque landscapes. Fortune seekers of every description —including Irish, German, Polish, Chinese, and African-American men—crowded the camps and boomtowns. A few hardy, business-minded women tried their luck too, working as laundresses, freight haulers, or miners. Cities such as Virginia City, Nevada, and Helena, Montana, originated as mining camps on Native American land.

The Government Restricts Native Americans

While allowing more settlers to move westward, the arrival of the railroads also influenced the government’s policy toward the Native Americans who lived on the plains. In 1834, the federal government had passed an act that designated the entire Great Plains as one enormous reservation, or land set aside for Native American tribes. In the 1850s, however, the government changed its policy and created treaties that defined specific boundaries for each tribe. Most Native Americans spurned the government treaties and continued to hunt on their traditional lands,clashing with settlers and miners—with tragic results.

KEY PLAYER : SITTING BULL (1831–1890)

As a child, Sitting Bull was known as Hunkesni, or Slow; he earned the name Tatanka Iyotanka(Sitting Bull) after a fight with the Crow, a traditional enemy of the Sioux.

Sitting Bull led his people by the strength of his character and purpose. He was a warrior, spiri-

tual leader, and medicine man,and he was determined that whites should leave Sioux territory. His most famous fight was at the Little Bighorn River. About his opponent, George Armstrong Custer, he said, “They tell me I murdered Custer. It is a lie. . . . He was a fool and rode to his death.”

After Sitting Bull’s surrender to the federal government in 1881, his dislike of whites did not change. He was killed by Native American police at Standing Rock Reservation in December 1890.

MASSACRE AT SAND CREEK

One of the most tragic events occurred in 1864. Most of the Cheyenne, assuming they were under the protection of the U.S. government, had peacefully returned to Colorado’s Sand Creek Reserve for the winter. Yet General S. R. Curtis, U.S. Army commander in the West, sent a telegram to militia colonel John Chivington that read, “I want no peace till the Indians suffer more.” In response, Chivington and his troops descended on the Cheyenne and Arapaho—about 200 warriors and 500 women and children—camped at Sand Creek. The attack at dawn on November 29, 1864 killed over 150 inhabitants, mostly women and children.

DEATH ON THE BOZEMAN TRAIL

The Bozeman Trail ran directly through Sioux hunting grounds in the Bighorn Mountains. The Sioux chief, Red Cloud (Mahpiua Luta), had unsuccessfully appealed to the government to end white settlement on the trail. In December 1866, the warrior Crazy Horse ambushed Captain William J.Fetterman and his company at Lodge Trail Ridge. Over 80 soldiers were killed. Native Americans called this fight the Battle of the Hundred Slain. Whites called it the Fetterman Massacre.Skirmishes continued until the government agreed to close the Bozeman Trail. In return, the Treaty of Fort Laramie, in which the Sioux agreed to live on a reservation along the Missouri River, was forced on the leaders of the Sioux in 1868. Sitting Bull (Tatanka Iyotanka), leader of the Hunkpapa Sioux, had never signed it. Although the Ogala and Brule Sioux did sign the treaty, they expected to continue using their traditional hunting grounds.

Bloody Battles Continue

The Treaty of Fort Laramie provided only a temporary halt to warfare.The conflict between the two cultures continued as settlers moved westward and Native American nations resisted the restrictions imposed upon them. A Sioux warrior explained why.

A PERSONAL VOICE GALL, A HUNKPAPA SIOUX

“ (We) have been taught to hunt and live on the game. You tell us that we must learn to farm, live in one house, and take on your ways. Suppose the people living beyond the great sea should come and tell you that you must stop farming, and kill your cattle, and take your houses and lands, what would you do? Would you not fight them? ”

—quoted in Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

RED RIVER WAR

In late 1868, war broke out yet again as the Kiowa and Comanche engaged in six years of raiding that finally led to the Red River War of 1874–1875. The U.S. Army responded by herding the people of friendly tribes onto reservations while opening fire on all others. General Philip Sheridan, a Union Army veteran, gave orders “to destroy their villages and ponies, to kill and hang all warriors, and to bring back all women and children.” With such tactics, the army crushed resistance on the southern plains.

GOLD RUSH

Within four years of the Treaty of Fort Laramie, miners began searching the Black Hills for gold. The Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho protested to no avail. In 1874, when Colonel George A. Custer reported that the Black Hills had gold “from the grass roots down,” a gold rush was on.

Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, another Sioux chief, vainly appealed again to government officials in Washington.

CUSTER’S LAST STAND

In early June 1876, the Sioux and Cheyenne held a sun dance, during which Sitting Bull had a vision of soldiers and some Native Americans falling from their horses. When Colonel Custer and his troops reached the Little Bighorn River, the Native Americans were ready for them. Led by Crazy Horse, Gall, and Sitting Bull, the warriors—with raised spears and rifles—outflanked and crushed Custer’s

troops. Within an hour, Custer and all of the men of the Seventh Cavalry were dead. By late 1876, however, the Sioux were beaten. Sitting Bull and a few followers took refuge in Canada, where they remained until 1881. Eventually, to prevent his people’s starvation, Sitting Bull was forced to surrender. Later, in 1885,he appeared in William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West Show.

The Government Supports Assimilation

The Native Americans still had supporters in the United States, and debate over the treatment of Native Americans continued. The well-known writer Helen Hunt Jackson, for example, exposed the government’s many broken promises in her 1881 book A Century of Dishonor. At the same time many sympathizers supported assimilation, a plan under which Native Americans would give up their beliefs

and way of life and become part of the white culture.

THE DAWES ACT

In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act aiming to “Americanize” the Native Americans. The act broke up the reservations and gave some of the reservation land to individual Native Americans—160 acres to each head of household and 80 acres to each unmarried adult. The government would sell the remainder of the reservations to settlers, and the resulting income would be used by Native Americans to buy farm implements. By 1932, whites had taken about two-thirds of the territory that had been set aside for Native Americans. In the end, the Native Americans received no money from the sale of these lands.

THE DESTRUCTION OF THE BUFFALO

Perhaps the most significant blow to tribal life on the plains was the destruction of the buffalo. Tourists and fur traders shot buffalo for sport. U.S. General Sheridan noted with approval that buffalo hunters were destroying the Plains Indians’ main source of food, clothing, shelter, and fuel. In 1800, approximately 65 million buffalo roamed the plains; by 1890, fewer than 1000 remained. In 1900, the United States sheltered, in Yellowstone National Park, a single wild herd of buffalo.

The Battle of Wounded Knee

The Sioux continued to suffer poverty and disease. In desperation, they turned to a Paiute prophet who promised that if the Sioux performed a ritual called the Ghost Dance, Native American lands and way of life would be restored. The Ghost Dance movement spread rapidly among the 25,000 Sioux on the

Dakota reservation. Alarmed military leaders ordered the arrest of Sitting Bull. In December 1890, about 40 Native American police were sent to arrest him. Sitting Bull’s friend and bodyguard, Catch-the-Bear, shot one of them. The police then killed Sitting Bull. In the aftermath, Chief Big Foot led the fearful Sioux away.

WOUNDED KNEE

On December 28, 1890, the Seventh Cavalry—Custer’s old regiment—rounded up about 350 starving and freezing Sioux and took them to a camp at Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota. The next day, the soldiers demanded that the Native Americans give up all their weapons. A shot was fired; from which side, it was not clear. The soldiers opened fire with deadly cannon.

Within minutes, the Seventh Cavalry slaughtered 300 unarmed Native Americans, including several children. The

soldiers left the corpses to freeze on the ground. This event, the Battle of Wounded Knee, brought the Indian wars—and an entire era—to a bitter end

Cattle Becomes Big Business

As the great herds of buffalo disappeared, and Native Americans were forced onto smaller and less desirable reserverations, horses and cattle flourished on the plains. As cattle ranchers opened up the Great Plains to big business, ranching from Texas to Kansas became a profitable investment.

VAQUEROS AND COWBOYS

American settlers had never managed large herds on the open range, and they learned from their Mexican neighbors how to round up, rope, brand, and care for the animals. The animals themselves, the Texas longhorns, were sturdy, short-tempered breeds accustomed to the dry grasslands of southern Spain. Spanish settlers raised longhorns for food and brought horses to use as work animals and for transportation. As American as the cowboy seems today, his way of life stemmed directly from that of those first Spanish ranchers in Mexico. The cowboy’s clothes, food, and vocabulary were heavily influenced by the Mexican vaquero, who was the first to wear spurs, which he attached with straps to his bare feet and used to control his horse. His chaparreras, or leather overalls, became known as chaps. He ate charqui, or “jerky”—dried strips of meat. The Spanish bronco caballo, or “rough

horse” that ran wild, became known as a bronco or bronc. The strays, or mesteños, were the same mustangs that the American cowboy tamed and prized. The Mexican rancho became the American ranch. Finally, the English words corral and rodeo were borrowed from Spanish. In his skills, dress, and speech, the Mexicanvaquero was the true forerunner of the American “buckaroo” or cowboy.

Despite the plentiful herds of Western cattle, cowboys were not in great demand until the railroads reached the Great Plains. Before the Civil War, ranchers for the most part didn’t stray far from their homesteads with their cattle. There were, of course, some exceptions. During the California gold rush in 1849, some hardy cattlemen on horseback braved a long trek, or drive, through Apache territory and across the desert to collect $25 to $125 a head for their cattle. In 1854,two ranchers drove their cattle 700 miles to Muncie, Indiana, where they put them on stock cars bound for New York City. When the cattle were unloaded in New York, the stampede that followed caused a panic on Third Avenue. Parts of the country were not ready for the mass transportation of animals.

GROWING DEMAND FOR BEEF

After the Civil War, the demand for beef skyrocketed, partly due to the rapidly growing cities. The Chicago Union Stock Yardsopened in 1865, and by spring 1866, the railroads were running regularly through Sedalia, Missouri. From Sedalia, Texas ranchers could ship their cattle to Chicago and markets throughout the East. They found, however, that the route to Sedalia presented several obstacles: including thunderstorms and rain-swollen rivers. Also,in 1866, farmers angry about trampled crops blockaded cattle in Baxter Springs, Kansas, preventing them from reaching Sedalia. Some herds then had to be sold at cut-rate prices, others died of starvation.

THE COW TOWN

The next year, cattlemen found a more convenient route. Illinois cattle dealer Joseph McCoy approached several Western towns with plans to create a shipping yard where the trails and rail lines came together. The tiny Kansas town of Abilene enthusiastically agreed to the plan. McCoy built cattle pens, a three-story hotel, and helped survey the Chisholm Trail—the major cattle route from San Antonio, Texas, through Oklahoma to Kansas. Thirty-five thousand head of cattle were shipped out of the yard in Abilene during its first year in operation. The following year, business more than doubled, to 75,000 head. Soon ranchers were hiring cowboys to drive their cattle to Abilene. Within a few years, the Chisholm Trail had worn wide and deep.

A Day in the Life of a Cowboy

The meeting of the Chisholm Trail and the railroad in Abilene ushered in the hey-day of the cowboy. As many as 55,000 worked the plains between 1866 and 1885. Although folklore and postcards depicted the cowboy as Anglo-American, about 25 percent of them were African American, and at least 12 percent were Mexican.The romanticized American cowboy of myth rode the open range, herding cattle and fighting villains. Meanwhile, the real-life cowboy was doing nonstop work.A DAY’S WORK A cowboy worked 10 to 14 hours a day on a ranch and 14 or more on the trail, alert at all times for dangers that might harm or upset the herds.Some cowboys were as young as 15; most were broken-down by the time they were 40. A cowboy might own his saddle, but his trail horse usually belonged to his boss. He was an expert rider and roper. His gun might be used to protect the herd from wild or diseased animals rather than to hurt or chase outlaws.

ROUNDUP

The cowboy’s season began with a spring roundup, in which he and other hands from the ranch herded all the longhorns they could find on the open range into a large corral. They kept the herd penned there for several days, until the cattle were so hungry that they preferred grazing to running away. Then the cowboys sorted through the herd, claiming the cattle that were marked with the brand of their ranch and calves that still needed to be branded. After the herd was gathered and branded, the trail boss chose a crew for the long drive.

THE LONG DRIVE

This overland transport, or long drive, of the animals of ten lasted about three months. A typical drive included one cowboy for every 250 to 300 head of cattle; a cook who also drove the chuck wagon and set up camp; and awrangler who cared for the extra horses. A trail boss earned $100 or more a month for supervising the drive and negotiating with settlers and Native Americans.

During the long drive, the cowboy was in the saddle from dawn to dusk. He slept on the ground and bathed in rivers. He risked death and loss every day of the drive, especially at river crossings, where cattle often hesitated and were swept away. Because lightning was a constant danger, cowboys piled their spurs, buckles, and other metal objects at the edge of their camp to avoid attracting lightning bolts. Thunder, or even a sneeze, could cause a stampede.

LEGENDS OF THE WEST

Legendary figures like James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok and Martha Jane Burke (Calamity Jane) actually never dealt with cows. Hickok served as a scout and a spy during the Civil War and, later, as a marshal in Abilene, Kansas. He was a violent man who was shot and killed while holding a pair of aces and a pair of eights in a poker game, a hand still known as the “dead man’s hand.” Calamity Jane was an expert sharpshooter who dressed as a man. She may have been a scout for Colonel George Custer.

The End of the Open Range

Almost as quickly as cattle herds multiplied and ranching became big business, the cattle frontier met its end. Overgrazing of the land, extended bad weather, and the invention of barbed wire were largely responsible.Between 1883 and 1887 alternating patterns of dry summers and harsh winters wiped out whole herds. Most ranchers then turned to smaller herds of highgrade stock that would yield more meat per animal. Ranchers fenced the land with barbed wire, invented by Illinois farmer Joseph F. Glidden. It was cheap and easy to use and helped to turn the open plains into a series of fenced-in ranches.The era of the wide-open West was over.

'Reference Room > History of America' 카테고리의 다른 글

| [ PDF ] THE AMERICANS: RECONSTRUCTION TO THE 21ST CENTURY (0) | 2020.05.06 |

|---|---|

| CH1-SE1. The Americas, West Africa, and Europe (0) | 2020.02.16 |

| Table of Contents - AMERICANS (0) | 2020.02.16 |